- 41

- 1

Sharing Ideas and Updates on LPG in Nigeria and related information to enable effective collaboration within the LPG Value Chain

NNPC GAS MASTER PLAN FOR 2026 - LPG EXPANSION IN NIGERIA

Nigeria is not short of gas. What Nigeria is short of is usable gas for everyday life. This single truth sits at the heart of the country’s energy contradiction. We are one of Africa’s largest gas reserve holders, a major exporter of natural gas, and a country with multiple gas-focused policy frameworks. Yet millions of Nigerians still cook with firewood, charcoal, and kerosene, fuels that are inefficient, unhealthy, and environmentally destructive. This is not a minor policy oversight. It is a structural failure. Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) has long been positioned as the bridge between Nigeria’s gas wealth and household energy needs. It is cleaner than biomass, safer than kerosene when properly handled, scalable without massive grid infrastructure, and immediately deployable. In theory, LPG should already be dominant in Nigerian kitchens. In practice, it is not.

To understand why, we must look beyond surface explanations and examine the issue through three lenses at once: the lived Nigerian reality, the technical nature of LPG, and the intent of Nigeria’s Gas Master Plan (GMP). Only when these perspectives are aligned can LPG move from policy ambition to national norm.

Nigeria’s Gas Paradox: Plenty Below Ground, Scarcity at Home

Nigeria’s gas story has always been framed at the macro level, reserves, exports, revenues, and power generation. For decades, gas was treated primarily as a by-product of oil production, something to be exported, flared, or monetised through large-scale projects. Domestic utilisation, particularly for households, was secondary.

This orientation shaped infrastructure development. Pipelines were designed to feed export terminals and power plants. Investment followed high-return, large-volume projects. Meanwhile, the everyday energy needs of households were met with whatever was cheapest and most accessible at the local level. The result is visible across the country. Firewood remains dominant in rural areas. Charcoal thrives in peri-urban zones. Kerosene persists despite its volatility and safety risks. These fuels are not chosen because Nigerians prefer them. They are chosen because they are familiar, accessible, and affordable in the short term.

LPG entered this landscape as an alternative, but not as a replacement system. It was layered onto an already broken structure without fully addressing the barriers that shape household decisions.

What LPG Really Is And Why It Matters

LPG is a mixture of propane and butane. Under pressure, it becomes liquid, allowing it to be stored and transported efficiently in cylinders. When released, it vaporises and burns with a clean, controllable flame. From a technical standpoint, LPG is exceptionally well-suited for cooking. It produces minimal smoke, generates consistent heat, and significantly reduces indoor air pollution. Globally, LPG has been a cornerstone of clean cooking transitions in countries facing similar challenges to Nigeria. In Nigeria, however, LPG has been misunderstood and misrepresented. It is often framed as a “modern” or “elite” fuel rather than a practical household necessity. This framing has consequences. When LPG is seen as aspirational rather than essential, policy urgency weakens and adoption slows. Health outcomes alone justify LPG adoption. Biomass cooking fuels contribute to respiratory diseases, eye irritation, and long-term lung damage. Women and children bear the brunt of these impacts. LPG addresses this immediately. Time efficiency also matters. LPG cooks faster, reduces fuel preparation time, and allows for better heat control. For households and small food businesses, time saved translates directly into productivity and income. Yet none of these benefits matter if LPG feels unsafe or inaccessible.

Safety, Perception, and the Trust Deficit

One of the biggest barriers to LPG adoption in Nigeria is fear. Stories of explosions circulate widely, often without context. While accidents do occur, they are rarely caused by LPG itself. They are the result of poor-quality cylinders, expired equipment, illegal refilling practices, and lack of consumer education. In countries where standards are enforced and consumers are properly informed, LPG is one of the safest household fuels available. Nigeria’s challenge lies in regulation and enforcement, not fuel chemistry. Weak oversight allows substandard cylinders into the market. Consumers are rarely taught basic safety practices. Regulators often intervene only after incidents occur. This reactive approach deepens mistrust and reinforces negative perceptions. Trust is central to energy transitions. People must feel safe before they feel motivated. Without a credible, visible safety ecosystem, LPG adoption will always stall.

The Gas Master Plan: Vision Meets Reality

Nigeria’s Gas Master Plan represents an explicit attempt to correct decades of imbalance. At its core, the GMP is built on several key pillars:

Domestic Gas Utilisation – prioritising gas use within Nigeria rather than treating it solely as an export commodity.

Infrastructure Development – expanding pipelines, storage, processing, and distribution capacity.

Market-Based Pricing and Investment – creating a commercially viable gas market that attracts private capital.

Regulatory and Institutional Reform – improving coordination, governance, and enforcement across the gas value chain.

Gas as a Transition Fuel – positioning gas as a bridge between high-emission fuels and a cleaner energy future.

LPG sits squarely within these pillars, particularly domestic utilisation and energy transition. It is the most direct way for gas policy to touch everyday lives. However, execution has lagged behind intent.

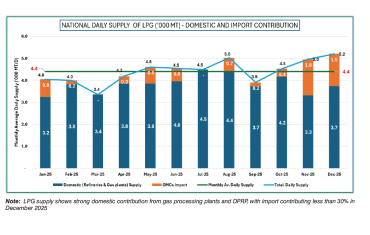

Infrastructure investment remains uneven. LPG storage and bottling facilities are concentrated in a few urban centres. Transportation logistics are costly and inefficient. As LPG moves inland, prices rise and availability drops.

Market dynamics are also constrained. Despite Nigeria’s gas reserves, LPG supply still depends partly on imports, exposing prices to foreign exchange volatility. This undermines affordability and price stability. Institutional fragmentation compounds these issues. Multiple agencies oversee different parts of the gas ecosystem, often with overlapping mandates. Coordination gaps slow progress and dilute accountability. The GMP acknowledges these challenges, but acknowledgement alone does not change outcomes.

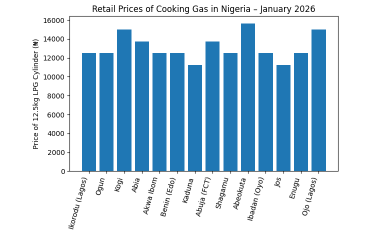

The Economics of LPG: Why Price Still Dominates the Conversation

For Nigerians, energy decisions are rarely ideological. They are financial. LPG pricing is influenced by several interconnected factors: international market trends, exchange rates, transportation costs, infrastructure gaps, and supply chain inefficiencies. One of the most significant barriers is the cost of entry. Cylinders, burners, and regulators require upfront investment. For households managing daily or weekly income, this initial cost can be prohibitive, even if LPG is cheaper over time.

Geography further shapes experience. Urban and coastal areas enjoy better supply and relatively lower prices. Rural and inland communities face higher costs and fewer refilling options. In these areas, firewood remains dominant not because it is better, but because it is available. LPG’s long-term cost efficiency is often lost in short-term realities. Nigerians do not budget energy annually; they budget daily. Until LPG fits into this rhythm, adoption will remain uneven.

LPG, Energy Transition, and Nigeria’s Realistic Path Forward

LPG is not a perfect solution. It is still a fossil fuel. It still emits carbon. In the long term, Nigeria must move toward cleaner, renewable cooking solutions.

But transitions are incremental. Countries do not leap from firewood to renewables overnight. They move through stages. Right now, LPG is Nigeria’s most realistic and scalable option. It delivers immediate health benefits. It reduces deforestation. It aligns with existing cooking habits. It does not require waiting decades for infrastructure transformation. For LPG to succeed, commitment must deepen. Government must treat LPG access as a social priority, not just an economic opportunity. Regulation must be consistent and visible. Infrastructure investment must extend beyond high-return urban markets. Financing models must lower entry barriers for households. The private sector must invest in safety, education, and distribution, not just margins. Consumers must be supported, not blamed. LPG is not the final destination. But it is the bridge Nigeria urgently needs between policy ambition and lived reality, between gas wealth and household dignity. Until LPG reaches Nigerian kitchens at scale, Nigeria’s gas story will remain incomplete.

Shalom

05 February 2026 - 01:20pmWe pray the GMP come through as stated ,this will be a game change in the LPG Industry .

Reply